A Kiss Goodbye: Axe Phoenix at Camp Socials

Also discussed: Wet Hot American Summer, our parents' divorce (sad), Sontag's Notes on Camp (obvi), Ben Affleck, Benjamin Nugent's 'Fraternity', and Jewish geography

With everything going on right now, it is nothing less than a *categorical imperative* that we discuss the prodigious use of Axe Phoenix at summer camp socials.

Joe: At Camp Menominee, in Eagle River, WI, the announcement—three or four times per four-week session—of a "social" with a girl's camp typically took place during dinner. But somehow you seemed to know before that. There was something in the air, a pleasant harbinger of something...off: Why were counselors showering before dinner? Why no set evening activities?! Why the whispered admonition “not to eat too much beanies and weenies”? ....and you’d start placing these puzzle pieces together (when was the last social? someone do the math!) but you almost didn’t dare utter the words…

And then the news would come like V-E Day: "Tonight we'll be joined by the beautiful girls across the lake at Camp Marimeta..." — and your appetite up and vanished, and you couldn't wait to be released, to join the entire camp in a mad dash down the hill towards the waterfront, where lines began to form for the showers. The dictum "don't forget to wash behind your ears," ringing in our ears...

Sam: Another dictum from the septuagenarian waterfront director about washing your “hangy-downy thing” also rang through your ears, if only because it added yet another entry to the already long list of funny names we had for our genitalia.

Joe: The very best moment, however, came in that intermediary time, when, after the showers, after dressing up in your finest ripped jeans and Abercrombie, you sat gingerly outside your cabin reveling in the nervous energy suffusing the early dusk: sun going down, a breeze coming off Sand Lake, that sense of purifying spent-ness after another taxing day playing in the summer heat. One could make out the whistling of the wind, the sounds of Green Day and Weezer playing from stereos, the muffled voices from neighboring cabins, maybe even a laconic paddle ball game...and then another sound, like the letting of air on your bike's tire...and the accompanying scent, joining the lush Wisconsin atmosphere…something indefinable…

…no, not citrus, not sweet, not woodsy, though perhaps a little like DEET…it tasted, when it got in your mouth, a bit like cocaine: brilliant and toxic. It was the smell of Axe Phoenix, so overpowering and over-applied it brushed up against irony, in that you might look to your friend or brother smelling it too and say, knowing full well there was about a zero percent chance of having any girl so much as hold your sweaty hand, "It's go time."

Sam: There was a giddy light-headedness to these moments, a feeling we would come to recognize as we cracked the first cold one before any big night out, a sense of potentiality you wanted to, for lack of a better metaphor, bottle up (and spray like hell).

We could hardly form sentences. Conversations revolved primarily around whether this or that dude knew this or that girl, and how well, and whether they might, you know, but like everything else in a dream they would sort of trail off, or never get going at all. Yet even as language failed us I rarely felt closer to my fellow man (boy) (primate?) during the hour or so before the girls’ arrival, when one minute seemed to melt so pleasantly into the next, and a kid had to wonder...is this the Axe Effect…in full effect?

Joe: In a word, yes? A lot of ink has been spilt about the psychology behind the so-called Axe Effect—the idea that the deodorant would, in and of itself, attract girls to you—and that this explained its popularity among tween boys like us. But I want to give us more (and less) credit than that. For like I said, we knew, simply based on the logistics of a camp social and our inexperience with girls, that no one really had any legitimate sexual interactions, at least at our age.

Sam: (Those who had were variably treated with quiet reverence and idle skepticism. Whether their stories were true or not, you just couldn’t believe it.)

Joe: Perhaps the application of Axe then was not about attracting girls but—and this is counterintuitive —repelling them: a classic, "reject you before you can reject me." For Axe Phoenix, I'll just say right now, smelled bad. It got so wrapped up in B.O. and its own reputation—“Oh, you're wearing Axe Phoenix?”—that even when we were still wearing it it telegraphed immaturity, inexperience, ludicrousness.

Sam: Came a time in the night when Axe succumbed to the collective power of pubescent boy underarm tang, the alchemical reaction of which would transmogrify the spray into the very stench it was designed to cover up. Like a Phoenix rising from its ashes, if the ashes were armpits.

Joe: Yeah, I mean, Axe Phoenix became almost inextricably tied, scentically (making up this word!), with teenage B.O. You might argue this rendered it moot as deodorant, but there’s another way to think of it. As preeminent smell essayist Rachel Syme writes in her latest piece about making sense of scents,

We might like to think we are most drawn to lovely, “clean” smells—laundry, linden blossoms, a eucalyptus breeze—but more often than not our greatest sensory delight comes from our most intimate, and most odiferous, nooks and crannies.

In other words, Axe Phoenix became as intimate and odiferous as our own B.O. There was a certain revelry in this. That's what it was about for us, I think. Embracing our own stink.

Sam: True. Although I hate to say you're "overthinking it," because overthinking is what this entire newsletter is predicated on—well, that, and referencing Lacan—but there's no way, even subconsciously, that we were spraying Axe Phoenix at such a grotesque clip in cabin 13 or whatever in order to “repel” girls. I don't know about you (what am I talking about, I totally do) but I deployed other, much more effective tactics to preempt rejection—namely, standing in a corner talking to you and our more sexually mature friend who claimed his penis wasn't big nor small but just "oddly shaped." I actually think he said it was shaped like a square? Or maybe that's just how I imagined it? I don't know. It was fucked up.

Joe: Of course we didn't want to consciously "repel" girls (what is Lacanian psychoanalysis even for?!?). But what I'm trying to say—and this is in the literature about Axe—

Sam: Ah yes, the “literature about Axe…”

Joe: —is that the socials were more homosocial than anything else, but not as dark as it’s often made out to be. For us, the ritual of Axe spraying wasn't, as this amazing Ben Affleck commercial would suggest, about impressing guys with the amount of girls we got so much as it was an acknowledgement of the sort of unreality of the endeavor itself. Or, the thrill. There was something comic about it. Like that absurd joke this one older kid kept making about us before and during every camp social, about wanting to film us having a three-way with a girl or something like that. I mean, that was just so far out of the realm of what was possible it wasn't even offensive.

Sam: Just have to say that Affleck using a clicker in an Axe commercial to tabulate how many women conveyed sexual interest in him on a single day is at once pitch-perfect self-parody and a rather prescient glimpse at the way social media would come to quantify popularity. (I love Affleck.)

But going back to Axe’s appeal…I just think we loved it for the same reason we loved socials, which is because they were both so straightforwardly associated with sex—and also a sort of prophylactic against actually having it. Those events were thrillingly stripped of any of the pretenses upon which the majority of pubescent interactions with the desired sex rely. But they were also way more chaste (at least for us).

Joe: Right, I mean, there was a refreshing obviousness to socials and Axe. Do you remember Axe Bombs? We would use the bottles as a literal weapon, messing with the spout so that it sprayed uncontrollably before launching it over the rafters into the next cabin. The excess feels apt for the Axe Bomb, and speaks to the sort of cosplaying at adulthood we were engaged in just by virtue of using Axe—when in reality it was just another toy.

Sam: Not to put too fine a point on it, but I actually think Axe is pure camp.

Joe: I mean, Sontag—

Sam: I really set you up for that one…

Joe: —in her Notes on Camp, quotes Oscar Wilde at the outset in such a way that he could be talking about Axe (lol): "One should either be a work of art, or wear a work of art."

Sam: *Sontag rolls over in her grave; says something to the effect of, “What’s next, are these guys going to apply On Photography to their Snapchats of cats?”*

Joe: The whole “Axe Effect”—it feels like it must be put in quotes, which is another way Sontag describes camp art—in its pure decorative style, its irony, absurdity, childishness...I mean, you can really stop at random within Sontag's text and find something that makes the case. But one section is particularly interesting, particularly when related to how Axe (and other male scents) are made, which, according to perfume expert Barbra Herman, is really just "like women's perfumes on steroids."

Camp taste draws on a mostly unacknowledged truth of taste: the most refined form of sexual attractiveness (as well as the most refined form of sexual pleasure) consists in going against the grain of one's sex. What is most beautiful in virile men is something feminine; what is most beautiful in feminine women is something masculine. . .

So while Axe might be resolutely masculine, perhaps it's really just a sort of stylized or "camp" version of femininity. Seen this way, our application of Axe before a camp social becomes almost like a subconscious self-feminization (or at least gender fluidity): let us become so manly with this Axe that we actually become feminine (or vice versa).

Sam: As I absorb this analysis I can’t help but hear the voice of a jacked bro in my head saying, "You've got a clit??? Well, I've got a penis!!!" There's something reductively biological (anatomical?) about the chemical composition of Axe—as if everything "male" is just something "female" in extremis....

Joe: The dynamic, though, feels foundational to all environments that are resolutely all-male: someone's got to play the woman.

Sam: Uhhh, can you say, Shakespeare?!?

Joe:

Sam: The anecdote that springs to mind is from our friends at a rival camp, who used to have jerk-off races in their bunks to see who could come the fastest. But our one friend couldn't even physically ejaculate yet, so he always lost? Which is kind of...tragic? And kind of a perfect metaphor for...something? (Note to self: Pen a short story about this called "Coming" and submit it to The Paris Review, stat!)

Joe: For me it’s the jokes made among my fraternity brothers. Certainly, some were homophobic, but I actually think a vast majority of the remarks made when no girls were around were just...gay? Ironically, the mere act of making that joke seemed like a defense mechanism designed explicitly not to out the underlying fact: that being in a fraternity is gay.

Speaking of The Paris Review (sick transition), a favorite story of mine is Benjamin Nugent’s “God” (also in his collection, Fraternity, which is great). In “God”, these frat bros are obsessed with this girl they call “God” because she wrote a poem about how she made their (v cool) bro Nutella prematurely ejaculate. It creates this aura around her, such that another kid in the frat can’t get it up with her; and eventually, when the narrator does bed her, he does so only by thinking of Nutella. The story is this perfect reversal/ interrogation of the cliché frat boy formula: not guys fucking girls as their boys egg them on, but guys not being able to fuck girls because they’re more obsessed (or in love) with their boys. From “God”:

We did three Delta Zeta Chi owl hoots, and the sound was soft and Celtic against the human grunts and synthesizer belches of the music, and I wished the final owl hoot would never fade, our eight arms seized up forever around our heads, our huddle rotating slowly, as all huddles do, the faces of my brothers spinning in the black light. I remembered the day my mother took me to the Boston planetarium when I was seven, how the constellations maypoled around a void.

In some perverse way, that’s what was happening for us at camp socials, too.

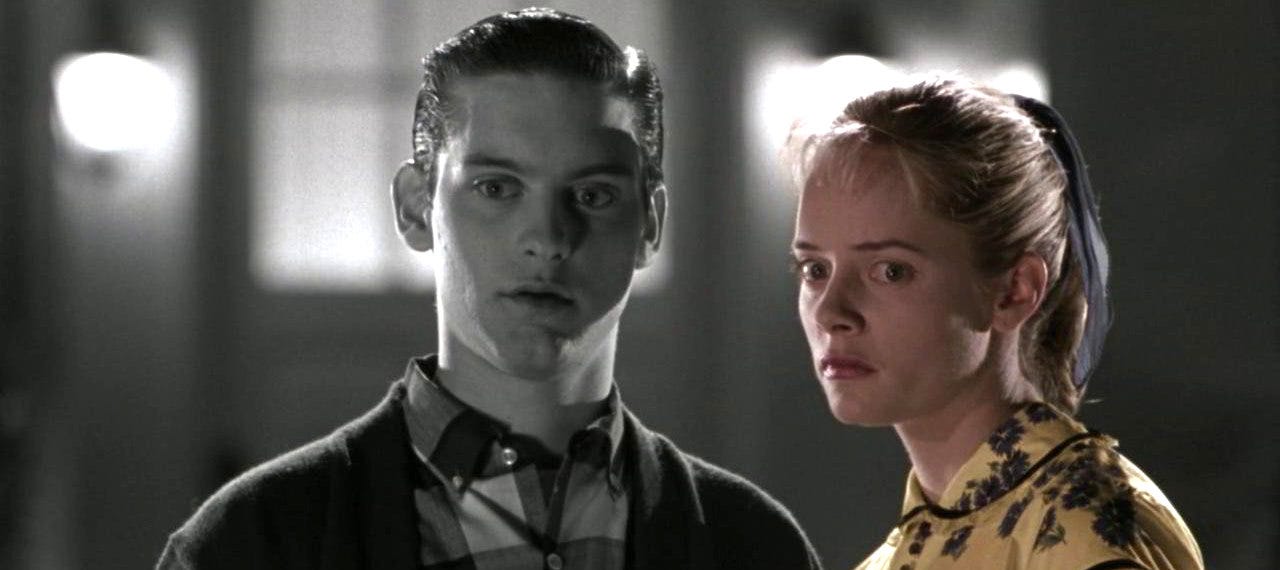

Sam: Yeah, minus the “owl hoots.” Also: The steamy gay sex scene in the shed between Ben and McKinley in Wet Hot American Summer is akin to shouting through a megaphone the quiet part about that dynamic out loud. It's perfect parody.

Joe: Wet Hot captures the ritualistic aspect of camp so well, too, perverting and stretching them into a kind of oblivion. The gum-chewing before making out comes to mind, naturally, as such a perfect encapsulation of the kind of unspoken contract that adolescent hook-ups require. Or another sort of ritual, like the Axe-wearing. You couldn’t just like, go in for it, it wasn’t that organic yet.

Sam: Although maybe it never is. Maybe the rituals just change; maybe they just become less obvious (and in some cases, more blurry).

I always return to the bit in Wet Hot when the counselors go to town. Everything starts out fine, they're getting fries and ice cream, and then little by little they descend into a kind of drug-addled Trainspotting-esque hell. And then they return to camp and Zak Orth delivers the kicker: "It's always fun to get away from camp, even for an hour." At the core of this bit is a kernel of truth: that heading into "town" after being in camp is kind of a jarring, surreal experience; and that camp, which is chock-full of incident, also distorts your perception of time, in a way it feels as though you've been there forever even though it's only been two weeks.

Joe: Camp had such a sealed-off quality, which in return reflected the sealed-off quality of the “real” lives of those who could afford to go to summer camp. It’s typified in those conversations we had before socials about, like, who knows who from where. After all, most of the camps around us were comprised of kids from the North and West suburbs of Chicago. And so we were essentially mapping a topography of those suburbs, not realizing in doing so that overnight camps in and of themselves are “suburban”: little planned towns in previously rural outposts filled with identical “houses”; a largely homogenous (and white, and upper-middle class (and Jewish, for us)) populace; and all of it glazed over with a certain innocence, coziness, repressiveness—a sense of safety, which, like Axe, masks something if not darker than at least more raw.

Sam: To be fair there really was nothing that dark about camp, at least not our experience of it. It was all about delaying what was (or had the potential) to be dark outside of camp, when we grew up. We had to manufacture our own drama.

Joe: Like when our cabin ratted this counselor out for the weed we found in his backpack. Sure, we didn’t like him, but we were also like, Maybe he’s such a dick because he’s high on the devil’s lettuce all the time. Which is such a privileged suburban kid mentality. Of course, in the most classic suburban twist of them all, we saw him at our town’s rec center a few years later and sincerely apologized. By then, I think one of our bunkmates had actually gone on to become a prominent pot dealer.

Sam: It was just such a bubble, not only geographically, or even in terms of gender and age, but simply in the sense of a collective purpose: Absolutely nothing but camp matters when you're at camp. So the shock of leaving camp at the end of any summer was strange, with the world changed somehow, almost like reentering a party after making out with someone on a bed covered in coats (presumably).

For us, this shock was intensified when we returned from camp one summer only to be told that our parents were getting a divorce, a moment so perfectly on-the-nose that my memory of it—which vaguely involves an image of a brand new Harry Potter book on both of our beds and us shuffling around the garage talking about it with our friend but not knowing really what to say so ultimately just, like, playing basketball or something—is cinematic to the point of seeming false.

Joe: Was it Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix? I actually think it was…

Sam: Wingardium leviosa! Anyway, I’m not sure we ever said it aloud, but I vividly recall us thinking, "Wow, really wish we could go back to camp right now.” But of course we couldn't. We'd already left, we couldn't return till next summer, instead we were whisked away on a doomed vacation to Aptos, California, where the weather was comically overcast, you got a participation trophy in some karate tournament, and try as we might the psychic power of camp, of our innocence, of everything before, couldn't prevent the onrush of reality coming to meet us on the other side...

Joe: I think camp taught you even as a kid that that sort of protected, safe, ebullient idyll of childhood would end—or did not exist—by creating a space where it existed more purely. And the socials offered one glimpse into the adulthood (i.e., sexual relations) that awaited us once our time at camp ended for good.

I remember getting so upset at you, in sixth grade, when I'd found out you kissed someone on the lifeguard bench at Rosewood Beach. I had no argument, I was grasping at straws, all of our (only two) friends knew I was being ridiculous, but I was angry, I would miss playing Manhunt on our block in the after-dinner hours, I would miss jumping tirelessly on friends' trampolines, playing whiffle ball in the cul-de-sac, basketball in the driveway. But even as I made these arguments I knew they were futile, that I was really staking a fight against getting older, becoming nostalgic for a childhood I saw slipping away, inevitably, and so I wasn't even angry at you as much as I was acting out against life: No, no, I'm not ready yet, just one more summer!

Oddly enough, though, I don't even think that was your first kiss. Maybe your first makeout. Our first kisses happened during a camp social. But we never counted them as such. Maybe because like everything at camp it felt more like a game than anything else, maybe because it was just a peck. I can't remember how it developed, just that we'd started talking to these two girls. What were our lines then? Did we have lines?

Sam: Did we ever have lines? It was probably something about us being twins. Didn’t we sing, like, Hilary Duff songs? Why? Still—take that, Axe Effect!

Joe: I just remember at some point they passed out desserts—popsicles, ice cream sandwiches, things like that. The night grew cool and dark, and beneath a makeshift pavilion a DJ-slash-v. cool counselor chanted on a mic over that Nelly song, “It’s getting hot in here, so keep on all your clothes,” his voice booming out from under some cheap automatic disco light. There was sand everywhere, brushing up against concrete, our ankles, our calves. And then the yellow school buses arrived—or had they been there all this time?—their headlights spilling into the tent: time to go, a slow wave of farewells as the sexes split.

The two girls we were talking to—I just remember the one I liked's name was, unbelievably (or falsely), Sushi—followed us to the bus. We didn't want to leave. But what else was there to do? What was the goal of a social for kids like us, immature, prude, sober? We could get their phone numbers, but Sushi—I don't even think Sushi lived in one of the suburbs near us. Time was running out. Goosebumps climbed up our arms. I can't remember how it happened. Do you? I feel like someone must have suggested it: a kiss goodbye. And that's all it was.

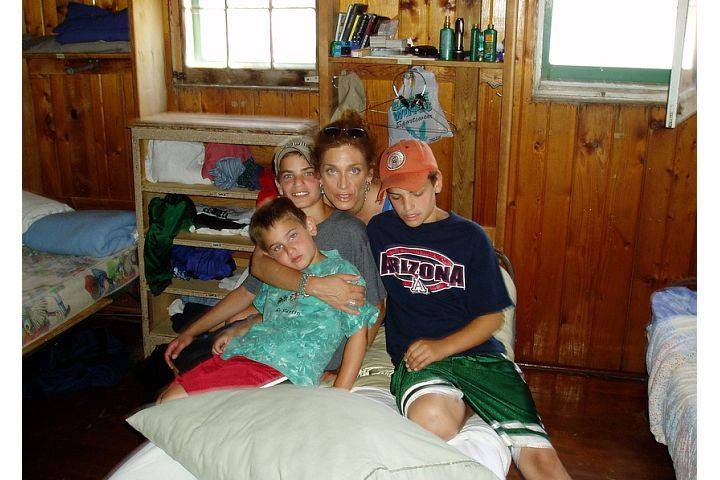

Loved it. I went to summer camp too and to the extent I can remember can relate. Also glad to know the deodorant I bought for you did not go to waste.

Lol at the Sontag picture and caption. I distinctly remember the smell of Axe combined with the blindingly fetid odor of karate and lacrosse clothes that had been enclosed in a gym bag for a week.