Remember going out?: On STIs in 'The Last Days of Disco'

Also discussed: Euripides, Frances Ha, EmRata working remotely at Soho House, Angelus Novus, (not) clubbing in Kreuzberg, Hannah Horvath, the end of an era

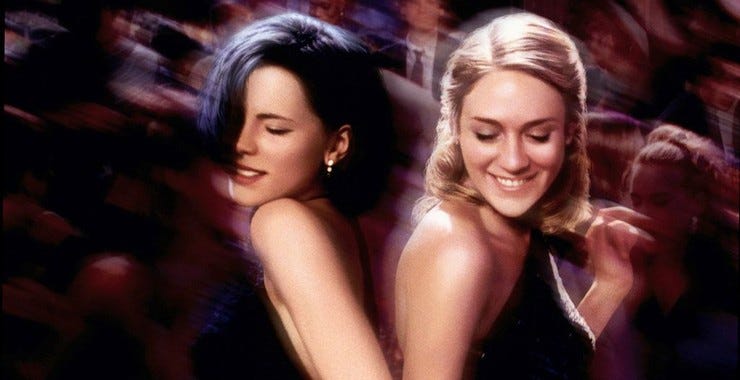

Directed by Whit Stillman, The Last Days of Disco (1998) trails a group of yuppies through their nights out at an early-80s New York discotheque, known only as The Club. With everything going on right now, let’s talk about the STIs—or the “g and h”—the film’s protagonist, Alice (Chloe Sevigny), contracts from a guy named Tom who’s really into Scrooge McDuck.

Joe: I rewatched this right after finishing up my Kant class at BISR—weird enough on its own—and I couldn’t help but think about the last class we took there, on Euripides.

Sam: Holy niche.

Joe: Remember Iphigenia at Aulis?

Sam: You paid more attention than I did.

Joe: Basically, Agamemnon's daughter, Iphigenia, is to be sacrificed to the gods to get Agamemnon's army out of a pointless war over Helena. Which reminded me of Alice in Disco: this young, innocent girl who feels as though she must sacrifice herself to uphold this pre-existing social order.

Yet the mere fact that she feels such a sense of duty speaks to the lunacy of that system, that society, and the ways in which it’s breaking down. And as we discussed re: Iphigenia — who, once she uncovers the situation, is like, “Yeah, sure, I'll sacrifice myself” — the question becomes: Is she heroic? Or delusional? I almost think you could say the same of Alice.

Sam: What you read as Alice’s “sacrifice” could, in a more realpolitik view, just be seen as her initiation into the group—the “group” being the literal gang of loosely associated college friends in Disco, their generation, and The Club itself, which is so fundamental to their social livelihood.

Joe: Yeah. Alice’s STIs are intimately (pun intended) tied to the social fabric of the group and the way the group sees itself. Here, again, though, I think of Euripides, and a note I took while reading a play about another — albeit very different — virtuous virgin, Hippolytus.

Sam: More Euripides?!?!

Joe: I wrote in my notebook —

Sam: You wrote in your notebook?!?! —

Joe: — that his "virginity is the desire for some other form of social organization, a longing for a mythical rather than merely embodied desire." And isn't this what Alice gets by contracting g and h? It almost recasts her as a virgin, if not of body than of soul; as Alice’s roommate Holly remarks (and I’m paraphrasing), "A guy would have to be so idealistic and in love with you he wouldn't even care." The notion is at once incredibly romantic, incredibly absurd, and incredibly conservative, which makes it perfect and transcendent satire, like the rest of the movie. I think it also explains Des's fascination with her, too. After all, what is is his oft-repeated speech about being affronted by a woman's large breasts but a sort of mystical, supranatural desire?

Sam: At the same time, one could argue Alice getting g and h allows her to skirt some of the obligations of twenty-something group dynamics (or “social organization”). She’s no longer able to seamlessly participate in the perpetual pairing off and breaking up that’s endemic in practically every group of friends between the ages of 15 and 25.

I’ve always believed Stillman captures this universal dance of "going out" in Disco better than any other director has—the merry-go-round of being part of a friend group, pairing off with one person, then reentering the group only to pair off with someone else. Pairing off is of course at odds with the group dynamic, and yet both rely on each other to function, until one-by-one pairs begin to get off the merry-go-round for good, settle down, have kids, etc. It’s natural evolution, and in the process an entire generation shifts, or turns over. In the final scene of the film, Des (Chris Eigeman) laments: “I mean if you’re already living with someone, why bother going out?” He’s really just coming to terms with growing up. Stillman never lets us forget that his characters are essentially children, whether it's Tom's thing for Scrooge McDuck, Josh's oversized clothes, or the group's exegesis of Lady and the Tramp.

Joe: Of course the ending, as you noted, mirrors the type of pairing off that happens at the end of a long night. But instead of the pairs forming after a party, they form in the harsh light of day, after a court appearance involving The Club. Des and Charlotte (Kate Beckinsale), who have heretofore never had any sort of attraction to one another —in fact, despite their self-proclaimed maturity in the game of love, they are anything but—end up pairing off almost by accident, in a coy, almost 7th grade, we’ll-just-leave-you-here-now way that befits the childishness permeating the film.

Sam: Like when your boys left you in the basement with the girl you liked because they “wanted to get a snack.”

Joe: So sick…I think, though, that Des’s lament about going out ultimately refigures The Club as a site that, contrary to its aura of maturity, temptation, and initiation (i.e., where Alice loses her virginity), is actually innocent, or was innocent, in the same way Des and Charlotte's playing at seasoned lothsarios is exposed as a basic naïveté about how the world actually works and the times they’re living in.

Sam: The tables have turned and though they’re left behind they (tragically?) think they’re still ahead of the game. Because nothing of any real consequence actually happens to Des and Charlotte, like it does to Josh and Alice. G and h—I mean, that’s not not a punishment. Unjust, too, because Alice, as a character, is rather blameless. During the night in question, Tom (Robert Sean Leonard) wants to sleep with Alice, but the fact that she gives in (and gets g and h) means he won’t sleep with her again, because it implies she's unserious—that all she wants is sex. Tom ridiculously takes this as evidence of how far the "sexual revolution" has gone.

The trap he sets for Alice is indicative of a patently intellectual yet undoubtedly conservative backlash to second-wave feminism—that is, Tom simultaneously wants the vixen and the virgin, someone who would sleep with a guy on the first date and someone who would never. Chloe Sevigny walks around looking stupefied a lot in this movie, and it's no wonder: How exactly should Alice be?

Joe: One might argue that her stupefaction demonstrates she's the only one in the movie who knows more than the other characters do. She seems at once ahead of the events of the film and behind them, a Stillman-esque Angel of History caught up in a storm that propels her into the future to which her back is turned, as the pile of burning disco records grows skyward. The monotonic passivity with which she receives the news of the g and h, at dinner with Tom, captures this feeling exactly: It's like she already knows that, in the grand scheme of things, gonorrhea can be knocked out with antibiotics and herpes isn't going to be so bad. She’s already past it. So are we.

Sam: But the film is acutely aware of all the stuff that is going to be bad. As Jimmy Steinway (Mackenzie Astin, half-brother of Rudy, lol) remarks after getting attacked outside The Club, it’s as if a “meteor” is heading straight for it. To which Des fatalistically says, "I don't know if it's a meteor…” And of course he's right. It's not a meteor, but all of these seismic socioeconomic shifts conspiring to bring about irrevocable change to the city. Maybe I’m just dense but every time I watch Disco I’m more in awe of how seamlessly it reveals so much about what's to come in the '80s, especially in New York—

Joe: As if you (we) weren’t born in 1991 —

Sam: —whether it's the club owner Bernie's personal greed (and Des's growing cocaine habit); the big business-friendly Koch-era policies that accelerated gentrification (Departmental Dan wonkily notes that the railroad apartment the girls live in used to be a tenement building); the rise of TV and decline of literary culture—

Joe: Not if this Substack has anything to say about it!

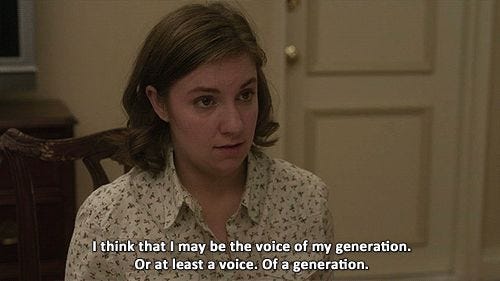

Sam: Or, in the case of Alice's STIs, the coming AIDS epidemic. The g and h are, of course, a dark omen. But in the movie, they’re treated as a trifle, even an inevitability. Not unlike how in Girls, when Hannah gets HPV, she embraces it as something all adventurous women have.

Joe: What’s special about this movie is that while most pieces of art would treat these kind of known omens—about a future the audience has already lived through—as a means to lard the work with melancholy or dread, Stillman treats them lightly, matter-of-factly, even callously. For it's not simply that we the audience know what's to come and so project a certain inevitability onto the characters; it's that the film itself, in the way it’s written and acted and scored and designed, knows it, too. And so it's not melancholy we feel, but blitheness, e.g., in how it treats homosexuality (via Des's recurrent gag) and STIs. This is what makes it so funny: We're all in the know. To me, the entire movie is encapsulated in the moment Alice — the virgin, playing the vixen — makes a joke about Scrooge McDuck that's funny for not being funny.

Sam: Your assessment here begins to describe Stillman’s sui generis tone—something so integral to his work and yet so difficult to pin down. I’d argue Stillman does for yuppie WASPs what Woody Allen did for yuppie Jews; his writing—erudite, grandiose, and bemused, sometimes disaffected, sometimes direct—is more or less shtick, by which I mean it's imbued with a sense of its own ridiculousness. (This is not the same as being ironic.) Both Wes Anderson and Noah Baumbach seem of a piece with Stillman, although Anderson is much more absurd —

Joe: And lighter, more twee —

Sam: Baumbach much more Jewish —

Joe: And darker.

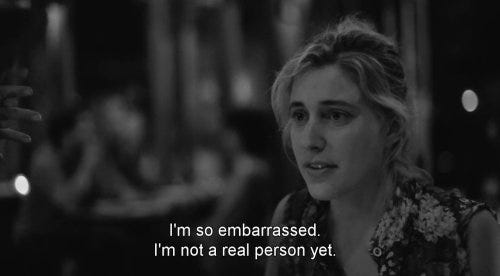

Sam: The closest kin Stillman has, aside from Jane Austen, may be Greta Gerwig, who happened to star in his underrated 2011 film, Damsels in Distress. "I wish I could live through something" and "Different things can be sad, it's not just war" from Lady Bird are such Stillman-esque lines, and the comically self-defeating Paris scene in Frances Ha is so up his alley. But whereas his characters are stuck precisely because they're already rich, Gerwig's characters are stuck precisely because they are not. Stillman's characters are bored, over-it; Gerwig's characters are striving, into-it. They’re *say it with me now* millennials.

No actor embodies Stillman’s milieu better than Eigeman, who plays Des in Disco, but also stars in the other two films of the director’s informal trilogy, Metropolitan and Barcelona, in addition to Baumbach's first feature, Kicking and Screaming. His characters bristle with—yet are exhausted by—their own intelligence, their imperious sense of rightness. They are pedantic, sardonic, clear-eyed in their hasty critiques but so irretrievably lost and sad as to come across pitiable, rank. They’re practically Dostoevskian. Watch this clip (start about a minute in) and tell me Eigeman is not one of the most under-appreciated actors of the ‘90s:

Joe: I do think what's central to both sides of the Gerwig-Stillman coin you've laid out, though, is a lack of stakes, or a wanting of stakes. And in a way that typifies the white middle-upper class artist making these films — a lack of stakes (and so: cool satire) or a wanting of stakes (and so: ironic melodrama).

Sam: I don’t know if I buy that. The stakes for the characters in Disco may be low but the themes it lays out are anything but. Same goes for Lady Bird.

Joe: I kind of feel like you could say that about anything? But either way. They tend to have an awkward, not-fitting-in-to-the-rich-kid-life quality to the characters in their movies that really resonates with me. It reminds me of that year or two you were a member of Soho House.

Sam: A brief yet indelible period in my life marked by $15 steak tartares, crippling social anxiety, and seeing Emily Ratajkowski “working remotely” once.

Joe: Right, I mean, I feel like whenever we were there (which was not that often), we were constantly asking ourselves: "Who actually feels like they belong here?"—

Sam: (Also, “What is anyone actually doing here?”)

Joe: —which is really just a rephrasing of Des's take on the term "yuppie": "For a group to exist someone has to admit to be a part of it." I mean, I feel like that all the time just in my own body.

Sam: I’m resisting a near-primal urge to summarize Mark Grief’s seminal New York Magazine piece about hipsters here.

Joe: Seminal! Speaking of, remember that night in Berlin when we so badly wanted to get into this club in Kreuzberg or wherever, and we were sure we were gonna get in because we'd met a couple of Spanish girls at the hostel who agreed to go with us?

Sam: How could I forget? It was the night before the morning we decided, over scrambled eggs and mushrooms, that rather than visit a concentration camp outside of the city, as we’d promised our mother, we’d go on a bar crawl with other tourists and try to get laid. After which your writer friend who admitted to both never brushing his teeth and only reading literary criticism (not literature) got a handjob in our shared room from some frustratingly hot Australian chick. While we called our mommy in the stairwell outside.

Joe: Proud and ashamed to say I think I was actually reading DFW’s Federer essay while the handjob was going on, which seems apt.

Sam: I think I was reading The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner on my Kindle at the time (great book), which I feel like maybe Kushner would appreciate.

Joe: …why?

Sam: Never mind.

Joe: Anyway, I’ll never forget when the bouncer at that club—a stoic woman in a big puffy yellow North Face or something—let all the Spanish girls through and then stopped us, and when we complained that we were with them, she said no, and when we kept complaining she said, in a tired, almost Alice-esque voice, "Just give up and move on."

Sam: She wasn’t even mad. She was just disappointed.

Joe: And that line, “give up and move on,” I mean, I remember repeating that ad infinitum, laughing. But now I kind of do feel like that about drinking and partying and stuff. Unless you’re in the top 1% of cool you reach a point where you just don’t belong anymore, where you’re either forcing it or an alcoholic.

Sam: I can't help but think about Disco in terms of everything going on right now…

Joe: Subscribe, please subscribe.

Sam:…particularly that last scene we've been coming back to, but even before that, when Van declares that "disco is over" and Josh delivers his emphatic speech. Because it's a movie, Stillman can dramatize the moment people realize something is over, that it's the end of an era. But in real life, of course, we're rarely aware of significant epochs ending as they end. I feel like everyone remembers the last bar or restaurant they drank or ate at before the pandemic really hit—for me, it was a cocktail at The Narrows, in Bushwick—

Joe: Or as I like to call it, “da wick”—

Sam: But even though those experiences were shot through with a sense of dread and anticipation, I don't know anyone who acknowledged, in that moment, the sheer gravity of what was to come. How could we? Insofar as Disco is simply a wistful love letter to going out...that really hits. Particularly given we're now 29 going on 30, "going out" feels further away than ever—as bygone an activity as summer camp socials. It doesn't feel like something we'll return to again, so much as something that's gone forever. And that's sad!

Joe: That’s one way of looking at it. Another way is to not view Disco as wistful at all. As I mentioned before, the audience knows it’s over before it even starts. And you can see that as sad or cynical or cold—all of which can be found in this movie (as Alice says to Charlotte: “I’m not even sure we really like each other”) —or you could see at as, I don’t know, joyous? Human?

Sam: What is it Charlotte says to Alice about her g and h? “C’mon, everyone gets something.”

I watched this movie for the first time before I read this. Because I love you boyz and it's a pandemic. I never actually thought about watching this movie because I actually lived this (although not nearly to the extent of this crew)--at that very same time and in those places (and I know you are most grateful that I won't go into detail about THAT)--and it was an incredibly fucking stupid time. And so for me the movie captures just the pure stupidity of it, the need to belong, the drugs, the pre-AIDS stds, and the spoiled silliness of it all. I love that you get into these big themes (I mean, Ipheginia!) but what this captures really well I think is the zeitgeist of the moment and kids that came of age in the "me" decade of the 70s (which of course led to the Reagan era and well, 40 years of narcissism culminating in he who shall not be named). But I digress. Always love a reference to Kant. P.S. I can't believe you never went to see the concentration camp.

As I get older, I now think it is better to be left in a dark basement with a girl than to be one of the cool guys going upstairs for snacks. You have a lifetime of snacks ahead of you—not so much dark basements with girls.